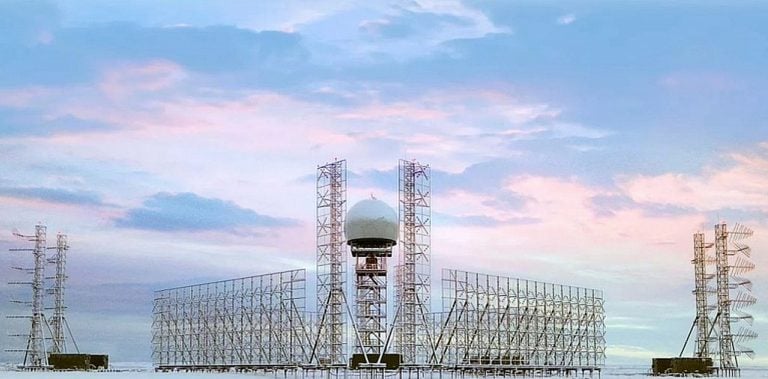

India’s air defense capabilities are currently a blend of advanced foreign systems and domestic technology, designed to address aerial threats from regional adversaries like Pakistan and China. The centerpiece of this framework is the Russian S-400 Triumf missile system, which India began deploying in 2021. Alongside this are indigenous systems such as the Akash missile, developed by the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), which provides short-to-medium range defense, and the joint Indo-Israeli Barak-8 missile system, capable of medium-range interception. Additional indigenous developments include the Quick Reaction Surface to Air Missile (QRSAM) and the upcoming XRSAM, reflecting India’s commitment to self-reliance in air defense.

As regional security dynamics evolve, notably with China’s advanced missile program—including hypersonic technologies—and ongoing tensions with Pakistan, India’s strategic considerations have become increasingly critical. The potential acquisition of the next-generation S-500 ‘Prometey’ system, developed by Russia’s Almaz-Antey defense company, is gaining attention. Designed to succeed the S-400, the S-500 boasts several advanced features, including the ability to intercept hypersonic missiles, ballistic threats, and even low-orbit satellites.

The S-500 Prometey can engage a plethora of targets simultaneously, boasting an engagement range of approximately 600 km for air threats and 500 km for ballistic missiles. Its advanced interceptors can reach high altitudes exceeding 185 km, enabling it to counter not just traditional aerial threats but also potential space-based attacks. Moreover, it has a significantly faster response time of 3-4 seconds compared to the S-400’s 9-10 seconds, adding to its tactical advantage in modern warfare scenarios.

India’s existing air defense framework is bolstered by several key systems:

- S-400 Triumf: This system, designed primarily to counter threats from Pakistan and China, can track over 100 targets and intercept threats up to 400 km away.

- Akash Missile System: With an indigenous content of about 96%, this system is adaptable and can engage multiple aerial threats, including drones.

- QRSAM: This rapid-deployment system protects against low-level aerial threats.

- XRSAM: Under development to enhance long-range surface-to-air capabilities.

- Barak-8: A joint venture with Israel, this system can intercept a range of threats from fighter jets to cruise missiles.

These systems collectively create a multi-layered defense architecture that aligns with India’s aims for defense autonomy as part of the ‘Make in India’ initiative.

Comparing the S-400 and S-500 reveals significant differences: the S-500 offers extended range, can track and engage a larger number of targets simultaneously, and has capabilities for interception of hypersonic threats and space-based systems. Additionally, its advanced radar technology enhances its effectiveness against stealth aircraft, indicating a substantial upgrade from the S-400.

The strategic advantages of acquiring the S-500 include enhancing defenses against both China and Pakistan, strengthening deterrence capabilities, potentially facilitating technology transfers with Russia, and preparing India for future conflicts characterized by advanced aerial threats. However, these benefits come with considerable challenges. The S-500 is likely to be more expensive than its predecessor, which could stretch India’s defense budget. Continued dependence on Russian technology raises geopolitical concerns amid evolving international relations and the potential for U.S. sanctions under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA).

Moreover, the recent induction of the S-400, combined with advancements in indigenous capabilities, may reduce the urgency for the S-500. The possibility also exists that a focus on acquiring such foreign systems could hinder the development of domestic projects, thus impacting long-term goals of self-reliance.

Geopolitically, while India maintains robust defense ties with Russia, a shift in focus to Western partnerships could bolster its technology and capabilities. This necessitates a careful balancing act between improving relations with Western allies and maintaining established ties with Russia.

Operationally, integrating the S-500 with existing systems presents both technological and logistical challenges. Effective utilization of its advanced capabilities will require sophisticated radar and surveillance networks, as well as a substantial investment in maintenance, training, and lifecycle support.

Considering alternatives to the S-500 could involve accelerating indigenous programs like the XRSAM or enhancing partnerships with Western countries for integrated air defense technologies. Investing in space and electronic warfare capabilities could also provide valuable complements to existing missile defense systems.

In conclusion, while the S-500 presents an exciting opportunity to elevate India’s air defense strategy, careful evaluation of the associated costs, geopolitical implications, and integration challenges is essential. A balanced approach that emphasizes long-term self-reliance, diversification of defense partnerships, and investment in indigenous initiatives may yield a more sustainable and robust defense posture for the future.