About 71 per cent of the planetary water is found in the oceans. The remaining is held as freshwater in glaciers and icecaps, groundwater sources, lakes, soil moisture, atmosphere, streams and within life. Nearly 59 per cent of the water that falls on land returns to the atmosphere through evaporation from over the oceans as well as from other places. The remainder runs-off on the surface, infiltrates into the ground or a part of it becomes glacier.

The Five Oceans

- The Arctic Ocean: The Arctic Ocean is divided by an underwater ocean ridge called the Lomonosov ridge into the 4,000-4,500 m deep Eurasian or Nasin basin and the 4,000 m deep North American or Hyperborean basin. The topography of the Arctic Ocean bottom varies consisting of fault-block ridges, abyssal plains, and ocean deeps and basins that have an average depth of 1,038 m due to the continental shelf on the Eurasian side.

- The Southern/Antarctic Ocean: The Southern Ocean is the world’s fourth-largest body of water. It encircles Antarctica and is actually divided among the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans. Most people of North America and Continental Europe have no name for the area and regard the area as parts of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans simply extending to Antarctica. However, because mariners have long referred to this area as the “Southern Ocean” it was accepted as an ocean in 2000 by the International Hydrographic Organization. This ocean is predominantly deep water, averaging 4,000-5,000 m deep, and includes the Antarctic continental shelf, an unusually deep and narrow area with an edge of 400-800 m deep (over 270-670 m deeper than average). The lowest point is 7,235 m deep at the southern end of the South Sandwich Trench.

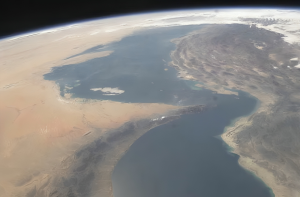

- The Indian Ocean: The Indian Ocean is the third largest in the world and makes up approximately 20% of the Earth’s water surface. It is bounded by southern Asia in the north, the Arabian Peninsula and Africa in the west, the Malay Peninsula, Sundra Islands and Australia in the east and the Southern Ocean in the south. The 20° east meridian separates the Indian Ocean from the Atlantic Ocean and the 147° east meridian separates it from the Pacific Ocean. The Indian Ocean stretches to about 30° N latitude in the Persian Gulf at its northernmost extent. At the southern tips of Africa and Australia, it is almost 10,000 km (or 6,200 miles) wide and its area is 73,556,000 km² (or 28,400,000 sq. miles) when the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf are included. The volume of this massive body of water has been estimated at 292,131,000 km³ (or 70,086,000 mi³). Other features include small islands around the continental rims such as Madagascar (the world’s fourth largest island), Comoros, Seychelles, Maldives, Mauritius, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia. The Indian Ocean is an important transit route between Asia and Africa, a geographical feature that has fuelled some strong historical conflicts. Because the Indian Ocean is so enormous, no nation had ruled it until the beginning of the 1800s when Britain was able to dominate much of the surrounding land.

- The Atlantic Ocean: The Earth’s second-largest ocean is the Atlantic, a name derived from the “Sea of Atlas” in Greek mythology. It covers approximately one-fifth of the entire global ocean. Water drains into the Atlantic from a land area four times the size of both the Pacific and Indian oceans. Excluding the neighbouring seas, the Atlantic has an average depth of 3,926 m (12,881 ft). The deepest area is found in the Puerto Rico Trench at 8,605 m or 28,232 ft. The Atlantic varies in width anywhere from a narrow 2,848 km between Brazil and Liberia to a wide 4,830 km between the United States and northern Africa.

- The Pacific Ocean: The Pacific Ocean covers a third of the Earth’s surface, has an area of 179.7 million km² and extends about 15,500 km from the Bering Sea in the Arctic all the way to the icy waters of Antarctica’s Ross Sea in the South. The Pacific is widest eastwards at 5° N latitude where it reaches all the way from Indonesia to the Columbian Coast, a distance of 19,800 km. Its farthest western point is most likely the Strait of Malacca. The Pacific Ocean also contains the lowest point on earth and deepest part of the Ocean known as the Mariana Trench, an area that is 10,911 m below sea level. There are 25,000 Pacific islands in the Pacific Ocean—more than any other ocean.

Relief Of The Ocean Floor

The oceans are confined to the great depressions of the earth’s outer layer. In this section, we shall see the nature of the ocean basins of the earth and their topography. The oceans, unlike the continents, merge so naturally into one another that it is hard to

demarcate them. The geographers have divided the oceanic part of the earth into five oceans, namely the Pacific, the Atlantic, the Indian, Southern ocean and the Arctic. The various seas, bays, gulfs, and other inlets are parts of these four large oceans. A major portion of the ocean floor is found between 3-6 km below the sea level. The ‘land’ under the waters of the oceans, that is, the ocean floor exhibits complex and varied features as those observed over the land. The floors of the oceans are rugged with the world’s largest mountain ranges, deepest trenches, and the largest plains. These features are formed, like those of the continents, by the factors of tectonic, volcanic, and depositional processes.

Division of Earth’s Floor

The ocean floors can be divided into four major divisions: (i) the Continental Shelf; (ii) the Continental Slope; (iii) the Deep-Sea Plain; (iv) the Oceanic Deeps. Besides, these divisions there are also major and minor relief features in the ocean floors like ridges, hills, sea mounts, guyots, trenches, canyons, etc.

- Continental Shelf: The continental shelf is the extended margin of each continent occupied by relatively shallow seas and gulfs. It is the shallowest part of the ocean showing an average gradient of 1° or even less. The shelf typically ends at a very steep slope, called the shelf break. The width of the continental shelves vary from one ocean to another. The average width of continental shelves is about 80 km. The shelves are almost absent or very narrow along some of the margins like the coasts of Chile, the west coast of Sumatra, etc. On the contrary, the Siberian shelf in the Arctic Ocean, the largest in the world, stretches to 1,500 km in width. The depth of the shelves also varies. It may be as shallow as 30 m in some areas while in some areas it is as deep as 600 m. The continental shelves are covered with variable thicknesses of sediments brought down by rivers, glaciers, wind, from the land and distributed by waves and currents. Massive sedimentary deposits received over a long time by the continental shelves, become the source of fossil fuels.

- Continental Slope: The continental slope connects the continental shelf and the ocean basins. It begins where the bottom of the continental shelf sharply drops off into a steep slope. The gradient of the slope region varies between 2-5°. The depth of the slope region varies between 200 and 3,000 m. The slope boundary indicates the end of the continents. Canyons and trenches are observed in this region.

- Deep Sea Plain/ Abyssal Plain: Deep sea plains are gently sloping areas of the ocean basins. These are the flattest and smoothest regions of the world. The depths vary between 3,000 and 6,000m. These plains are covered with fine-grained sediments like clay and silt.

- Oceanic Deeps or Trenches: These areas are the deepest parts of the oceans. The trenches are relatively steep sided, narrow basins. They are some 3-5 km deeper than the surrounding ocean floor. They occur at the bases of continental slopes and along island arcs and are associated with active volcanoes and strong earthquakes. That is why they are significant in the study of plate movements. As many as 57 deeps have been explored so far; of which 32 are in the Pacific Ocean; 19 in the Atlantic Ocean and 6 in the Indian Ocean.

Minor Relief Features

Apart from the above-mentioned major relief features of the ocean floor, some minor but significant features predominate in different parts of the oceans.

- Mid-Oceanic Ridges: A mid-oceanic ridge is composed of two chains of mountains separated by a large depression. The mountain ranges can have peaks as high as 2,500 m and some even reach above the ocean’s surface. Iceland, a part of the mid- Atlantic Ridge, is an example.

- Seamount: It is a mountain with pointed summits, rising from the seafloor that does not reach the surface of the ocean. Seamounts are volcanic in origin. These can be 3,000-4,500 m tall. The Emperor seamount, an extension of the Hawaiian Islands in the Pacific Ocean, is a good example.

- Submarine Canyons: These are deep valleys, some comparable to the Grand Canyon of the Colorado river. They are sometimes found cutting across the continental shelves and slopes, often extending from the mouths of large rivers. The Hudson Canyon is the best-known submarine canyon in the world.

- Guyots: It is a flat-topped seamount. They show evidences of gradual subsidence through stages to become flat topped submerged mountains. It is estimated that more than 10,000 seamounts and guyots exist in the Pacific Ocean alone.

- Atoll: These are low islands found in the tropical oceans consisting of coral reefs surrounding a central depression. It may be a part of the sea (lagoon), or sometimes form enclosing a body of fresh, brackish, or highly saline water.

Horizontal Temperature Distribution of Oceanic Waters

The factors which affect the distribution of temperature of ocean water are:

- Latitude: the temperature of surface water decreases from the equator towards the poles because the amount of insolation decreases poleward. Since the earth is a geoid resembling a sphere, the sun’s rays strike the surface at different angles at different places. This depends on the latitude of the place. The higher the latitude, the less is the angle they make with the surface of the earth. The area covered by the vertical rays is always less than the slant rays. If more area is covered, the energy gets distributed and the net energy received per unit area decreases. Moreover, the sun’s rays with small angle traverse more of the atmosphere than rays striking at a large angle. Longer the path of the sun’s rays, greater is the amount of reflection and absorption of heat by the atmosphere. As a result, the intensity of insolation is less.

- Unequal Distribution of Land & Water: the oceans in the northern hemisphere receive more heat due to their contact with larger extent of land than the oceans in the southern hemisphere.

- Prevailing Wind: the winds blowing from the land towards the oceans drive warm surface water away from the coast resulting in the upwelling of cold water from below. It results into the longitudinal variation in the temperature. Contrary to this, the onshore winds pile up warm water near the coast and this raises the temperature.

- Ocean Currents: warm ocean currents raise the temperature in cold areas while the cold currents decrease the temperature in warm ocean areas.

Vertical Temperature Distribution of Oceanic Waters

The temperature-depth profile for the ocean water shows how the temperature decreases with the increasing depth. The profile shows a boundary region between the surface waters of the ocean and the deeper layers. The boundary usually begins around 100 – 400 m below the sea surface and extends several hundred of metres downward. This boundary region, from where there is a rapid decrease of temperature, is called the thermocline. About 90 per cent of the total volume of water is found below the thermocline in the deep ocean. In this zone, temperatures approach 0° C. The temperature structure of oceans over middle and low latitudes can be described as a three-layer system from surface to the bottom.

- The first layer represents the top layer of warm oceanic water and it is about 500m thick with temperatures ranging between 20° and 25° C. This layer, within the tropical region, is present throughout the year but in mid latitudes it develops only during summer.

- The second layer called the thermocline layer lies below the first layer and is characterised by rapid decrease in temperature with increasing depth. The thermocline is 500 – 1,000 m thick.

- The third layer is very cold and extends upto the deep ocean floor. In the Arctic and Antarctic circles, the surface water temperatures are close to 0° C and so the temperature change with the depth is very slight. Here, only one layer of cold water exists, which extends from surface to deep ocean floor.

Salinity Of Ocean Waters

All waters in nature, whether rainwater or ocean water, contain dissolved mineral salts. Salinity is the term used to define the total content of dissolved salts in sea water (Table 13.4). It is calculated as the amount of salt (in gm) dissolved in 1,000 gm (1 kg) of seawater. It is usually expressed as parts per thousand (o/oo) or ppt. Salinity is an important property of sea water. Salinity of 24.7 o/oo has been considered as the upper limit to demarcate ‘brackish water’. Factors affecting ocean salinity are mentioned below:

- The salinity of water in the surface layer of oceans depend mainly on evaporation and precipitation.

- Surface salinity is greatly influenced in coastal regions by the freshwater flow from rivers, and in polar regions by the processes of freezing and thawing of ice.

- Wind also influences salinity of an area by transferring water to other areas.

- The ocean currents contribute to the salinity variations. Salinity, temperature and density of water are interrelated. Hence, any change in the temperature or density influences the salinity of water in an area.

- Horizontal

Distribution of Salinity: The surface salinity of oceans decreases on either side of the

tropics. For instance, the surface salinity along the Tropic of Cancer is around

36 parts per thousand (ppt) while at the equator it is around 35 parts per

thousand. On the basis of their salinity levels, seas across the world can be

categorized as follows:

- Seas with salinity levels below the normal: They have a low salinity due to the influx of fresh water. They include the Arctic Ocean, Southern Ocean, Bering Sea, Sea of Japan, Baltic Sea etc. Their surface salinity can be as low as 21 ppt.

- Seas with normal salinity levels: These have a salinity in the range of 35 to 36 ppt. They include the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, Gulf of California, Yellow Sea etc.

- Seas with salinity levels above the normal: They have higher levels of salinity because of their location in regions with higher temperatures leading to greater evaporation. They include the Red Sea (39 – 41 ppt), Persian Gulf (38 ppt), Mediterranean Sea (37 – 39 ppt) etc.

- Vertica Distribution of Salinity: There is no definite trend in the variation of salinity with depth. Instances of increase, as well as a decrease in salinity levels, have been found with increasing depth.

Tidal Waves and Tide Formation

Based on the Position of Earth, Sun, and the Moon, tides can be Spring Tides or Neap Tides.

- Spring Tides: Spring tides are formed when the sun and the moon are in line with each other and pull the ocean surface in the same direction. This leads to higher high tides and lowers low tides and such tide is called a spring tide. In a lunar month, it occurs twice. It is also known by the name of ‘King Tide.’ Note: The aspirants should know that the spring season has nothing to do with spring tides. The word ‘Spring’ in spring tides means ‘springing forth.’ These occur in full or new moon days. In both new moon or full moon days, the sun’s gravitational pull is added to the moon’s gravitational pull on Earth, causing the oceans to bulge a bit more than usual. This results in ‘higher’ high tides and ‘lower’ low tides.

- Neap Tides: It occurs seven days after the spring tide. The prominent point is that the sun and the moon are at the right angle to each other. This tide occurs during the first and the last quarter of the moon. The gravitational pull of the moon and the resulting oceanic bulge is cancelled out by the gravitational pull of the sun and its resulting oceanic bulge. Also, in contrast to spring tides, the high tides are ‘lower’ and the low tides are comparatively ‘higher’ in neap tides.

Tides raise the level of seawater and hence exposes a large part of the ocean for erosion. It is helpful for the tidal ports that have shallow water which is a constraint for the big ships to enter. Tidal currents are a very potential source of tidal energy which is harnessed by many developed countries on an exceptionally large scale and to some extent in India as well. It can be devastating in cases where the tide gets too huge and results in the flooding of the nearby coastal regions. Tides are extremely helpful for ecosystems such as the mangrove forests and coral reefs to grow and sustain.

Atmospheric Wind Circulation

Friction between the wind and the water surface affects the movement of the water body in its course.

Coriolis Force

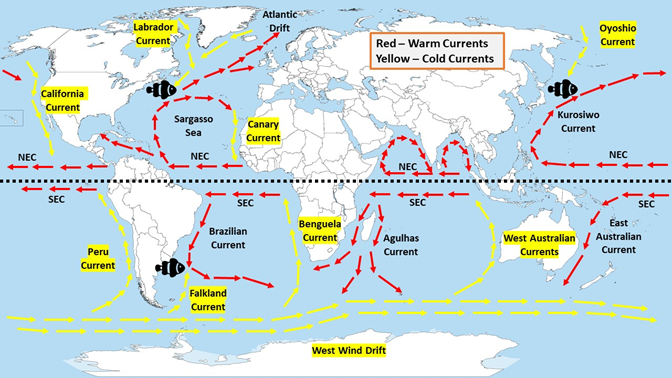

According to Ferrell’s law- Coriolis forces deflect winds and freely moving objects to the right in the northern hemisphere and to the left in the southern hemisphere. Therefore, the movement of ocean currents in the northern hemisphere is in the clockwise and in the southern hemisphere it is in the anti-clockwise direction.

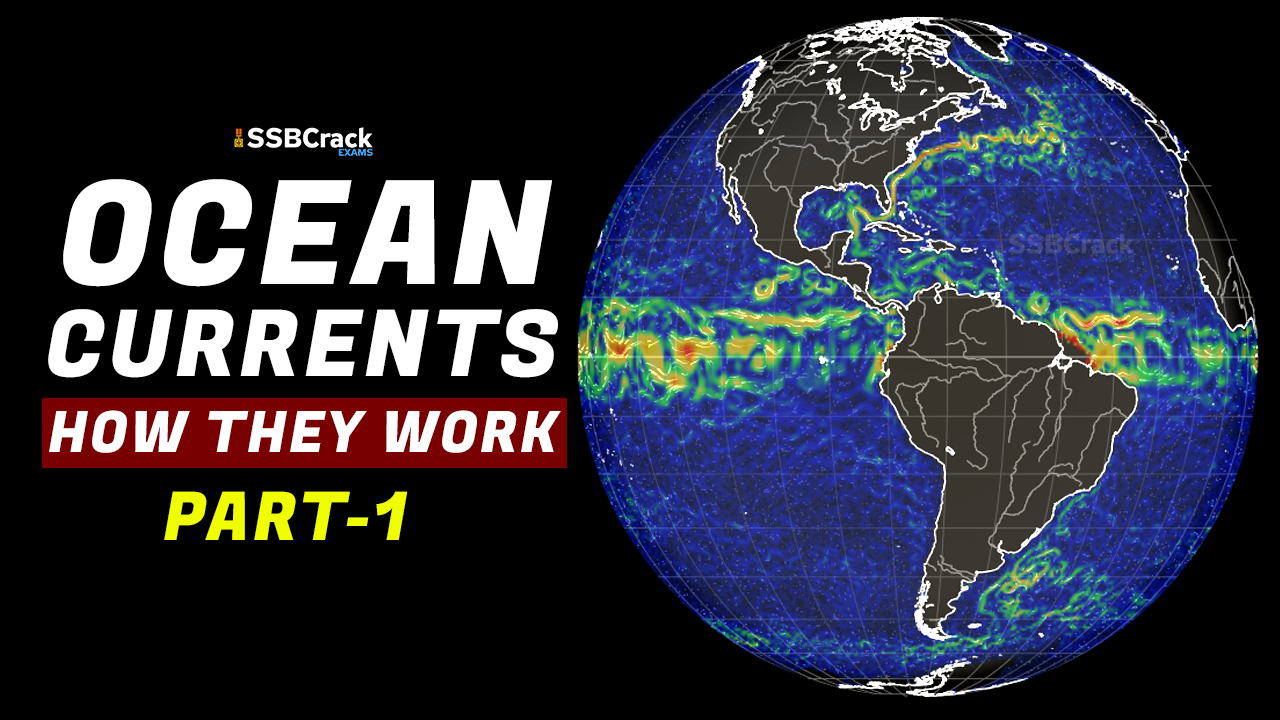

Ocean Currents

Ocean currents are like river flow in oceans. They represent a regular volume of water in a definite path and direction. Ocean currents are influenced by two types of forces namely:

- primary forces that initiate the movement of water.

- secondary forces that influence the currents to flow.

The primary forces that influence the currents are:

- heating by solar energy.

- wind.

- gravity.

- coriolis force.

Heating by solar energy causes the water to expand. That is why, near the equator the ocean water is about 8 cm higher in level than in the middle latitudes. This causes a very slight gradient and water tends to flow down the slope. Wind blowing on the surface of the ocean pushes the water to move. Friction between the wind and the water surface affects the movement of the water body in its course. Gravity tends to pull the water down the pile and create gradient variation. The Coriolis force intervenes and causes the water to move to the right in the northern hemisphere and to the left in the southern hemisphere. These large accumulations of water and the flow around them are called Gyres. These produce large circular currents in all the ocean basins.

Differences in water density affect vertical mobility of ocean currents. Water with high salinity is denser than water with low salinity and in the same way cold water is denser than warm water. Denser water tends to sink, while relatively lighter water tends to rise. Cold-water ocean currents occur when the cold water at the poles sinks and slowly moves towards the equator. Warm-water currents travel out from the equator along the surface, flowing towards the poles to replace the sinking cold water.

Types of Ocean Currents

The ocean currents may be classified based on their depth as surface currents and deep-water currents:

- Surface currents constitute about 10 per cent of all the water in the ocean, these waters are the upper 400 m of the ocean.

- Deep water currents make up the other 90 per cent of the ocean water. These waters move around the ocean basins due to variations in the density and gravity. Deep waters sink into the deep ocean basins at high latitudes, where the temperatures are cold enough to cause the density to increase.

Ocean currents can also be classified based on temperature : as cold currents and warm currents:

- cold currents bring cold water into warm water areas. These currents are usually found on the west coast of the continents in the low and middle latitudes (true in both hemispheres) and on the east coast in the higher latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere.

- Warm currents bring warm water into cold water areas and are usually observed on the east coast of continents in the low and middle latitudes (true in both hemispheres). In the northern hemisphere they are found on the west coasts of continents in high latitudes.

Major Ocean Currents: Major ocean currents are greatly influenced by the stresses exerted by the prevailing winds and coriolis force. The oceanic circulation pattern

roughly corresponds to the earth’s atmospheric circulation pattern. The air circulation over the oceans in the middle latitudes is mainly anticyclonic (more pronounced in the southern hemisphere than in the northern hemisphere). The oceanic circulation pattern also corresponds with the same. At higher latitudes, where the wind flow is mostly cyclonic, the oceanic circulation follows this pattern. In regions of pronounced monsoonal flow, the monsoon winds influence the current movements. Due to the coriolis force, the warm currents from low latitudes tend to move to the right in the northern hemisphere and to their left in the southern hemisphere. The oceanic circulation transports heat from one latitude belt to another in a manner similar to the heat transported by the general circulation of the atmosphere. The cold waters of the Arctic and Antarctic circles move towards warmer water in tropical and equatorial regions, while the warm waters of the lower latitudes move poleward. The major currents in the different oceans are shown in Figure.

Effects of Ocean Currents: Ocean currents have a number of direct and indirect influences on human activities. West coasts of the continents in tropical and subtropical latitudes (except close to the equator) are bordered by cool waters. Their average temperatures are relatively low with a narrow diurnal and annual ranges. There is fog, but generally the areas are arid. West coasts of the continents in the middle and higher latitudes are bordered by warm waters which cause a distinct marine climate. They are characterised by cool summers and relatively mild winters with a narrow annual range of temperatures. Warm currents flow parallel to the east coasts of the continents in tropical and subtropical latitudes. This results in warm and rainy climates. These areas lie in the western margins of the subtropical anti-cyclones. The mixing of warm and cold currents help to replenish the oxygen and favour the growth of planktons, the primary food for fish population. The best fishing grounds of the world exist mainly in these mixing zones.