The 9-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court held that the government cannot acquire and redistribute all privately owned properties deeming them “material resources of the community”, as mentioned in Article 39(b) of the Constitution. The 429-page judgment of the nine-judge Constitution bench headed by Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud lent clarity on the interpretation of Articles 31C and 39(b) of the Constitution, crucial provisions regarding the rights of individuals against the state’s authority to control resources for public good.

Govt Can’t Acquire All Private Properties : Supreme Court

Why In News

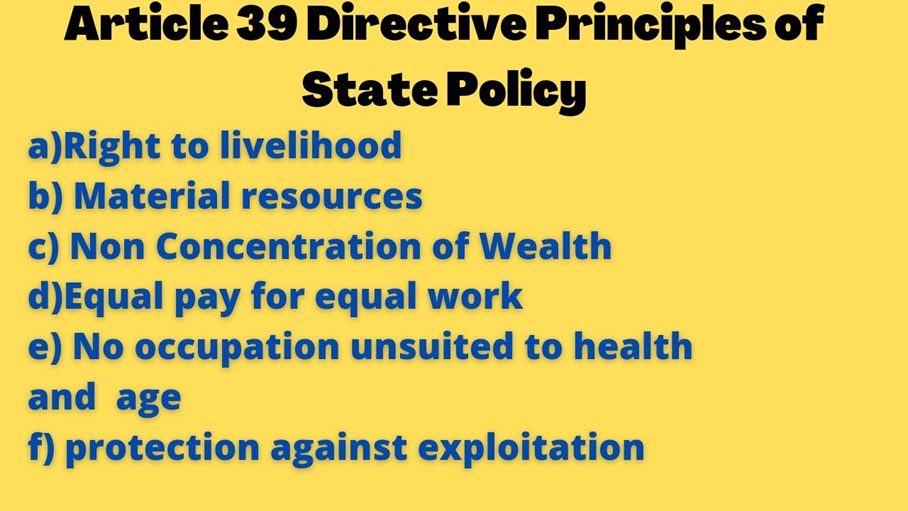

- The 9-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court held that the government cannot acquire and redistribute all privately owned properties deeming them “material resources of the community”, as mentioned in Article 39(b) of the Constitution. The 429-page judgment of the nine-judge Constitution bench headed by Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud lent clarity on the interpretation of Articles 31C and 39(b) of the Constitution, crucial provisions regarding the rights of individuals against the state’s authority to control resources for public good.

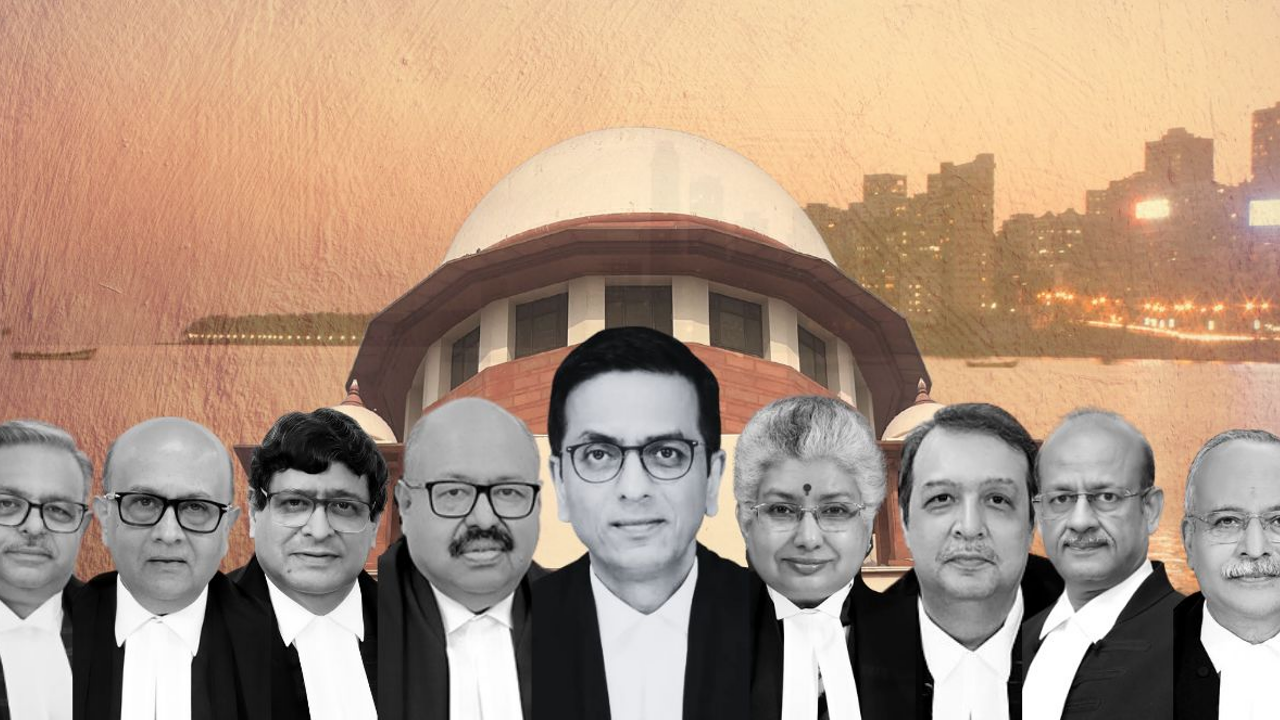

About Bench

- The Bench, comprising Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud, Justices Hrishikesh Roy, BV Nagarathna, Sudhanshu Dhulia, JB Pardiwala, Manoj Misra, Rajesh Bindal, Satish Chandra Sharma, and Augustine George Masih.

Case Background

- The case dates back to 1992 and was referred to a nine-judge bench in 2002, reflecting a prolonged deliberation over whether privately owned resources should be included in the definition of “material resources of the community” under Article 39(b).

- The majority verdict did not concur with the view expressed by Justice Krishna Iyer in the case of Ranganatha Reddy of 1978 wherein it was held that private property could be regarded as community resources.

- The petitioners argued that “material resources” should encompass any resource capable of generating wealth for the community’s benefit.

- They contended that if the law intended to include private properties, the language would have explicitly reflected that to prevent misinterpretation. The bench, in its conclusions, upheld Article 31C, which provided immunity to certain laws from judicial scrutiny, “to the extent that it was upheld in Kesavananda Bharati v Union of India remains in force”.

- The Kesavananda Bharati judgment had held that “the first half of Article 31C granting immunity to laws enacted in furtherance of clauses (b) or (c) of Article 39 (on taking over of properties) against challenges based on Articles 14,19 and 31 was valid” and the second half of the article excluding judicial review over whether a law in truth furthers the principles set out in clauses (b) or (c) of Article 39 was struck down.

- “The term ‘distribution’ has a wide connotation. The various forms of distribution which can be adopted by the state cannot be exhaustively detailed.

- However, it may include the vesting of the resources concerned in the state or nationalisation. In the specific case, the court must determine whether the distribution ‘subserves the common good’,” it said The top court had heard 16 petitions, including the lead petition filed by the Mumbai-based Property Owners’ Association in 1992.

Judgement

- This interpretation directly impacts how the government can redistribute resources for the “common good”.

- The court clarified that only certain types of private property, based on their nature, significance and impact on public welfare, could potentially fall under this provision, marking a departure from previous, more expansive interpretations rooted in socialist ideals. ourt stated that while certain private properties could fall under Article 39(b) if they serve the community’s needs, not all privately owned resources qualify for redistribution to promote the ‘common good’.

- The decision arose from the case of Property Owners Association and Ors v State of Maharashtra and Ors.

- The Court further explained that the determination of whether a resource falls under Article 39(b) must be context-specific and based on a range of factors, including:

- The nature of the resource.

- Its impact on the well-being of the community.

- Its scarcity.

- The consequences of the resource being concentrated in private hands.

Justice Dhulia Dissent

- Justice Dhulia’s dissent contended that excluding privately-owned properties from the purview of Article 39(b) disregards the practical reality that certain private resources might indeed benefit the public if distributed equitably. He argued that any blanket rejection of private resources within Article 39(b) risks undermining the Directive Principles’ broader intent.

Conclusion

- The judgement comes against the backdrop of rising income inequality in the country. According to experts, the ruling doesn’t completely bar the government from making policy on wealth distribution. However, it restricts its powers.