In its first, the Supreme Court, through its judgment dated March 21, has recognized a right to be free from the adverse effects of climate change as a distinct right. The Court said that Articles 14 (equality before law and the equal protection of laws) and 21 (right to life and personal liberty) of the Indian Constitution are important sources of this right.

Right To Be Free From Adverse Effects Of Climate Change

Why In News

- In its first, the Supreme Court, through its judgment dated March 21, has recognized a right to be free from the adverse effects of climate change as a distinct right. The Court said that Articles 14 (equality before law and the equal protection of laws) and 21 (right to life and personal liberty) of the Indian Constitution are important sources of this right.

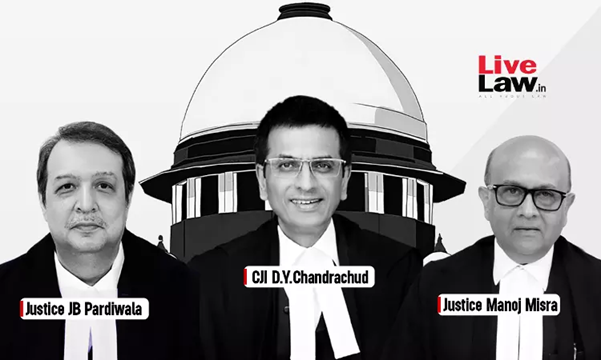

- The judgment by a three-judge Bench of Chief Justice of India (CJI) D Y Chandrachud and Justices J B Pardiwala and Manoj Misra, was delivered on March 21 in a case relating to the conservation of the critically endangered Great Indian Bustard (GIB). The judgment was made public on Saturday.

- The Bench noted that the intersection of climate change and human rights has been put into sharp focus in recent years, underscoring the imperative for states to address climate impacts through the lens of rights.

What Was The Case

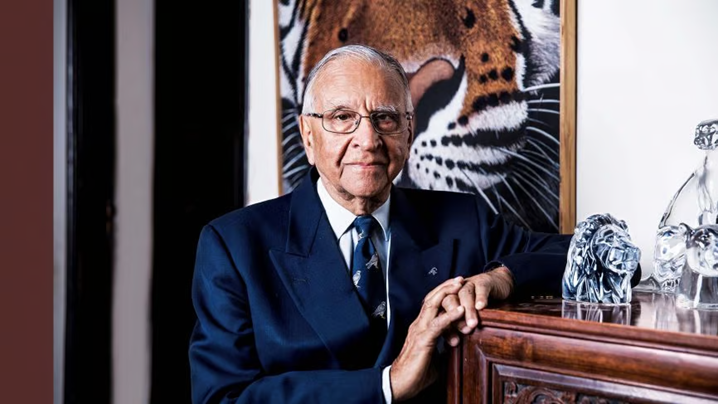

- The apex court’s ruling came in a writ petition filed by retired government official and conservationist M K Ranjitsinh, seeking protection for the GIB and the Lesser Florican, which are on the verge of extinction.

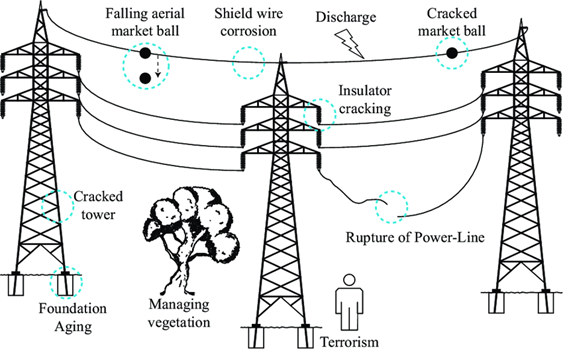

- The plea sought, among other things, the framing and implementation of an emergency response plan for the protection and recovery of the GIB — including directions for installation of bird diverters, an embargo on the sanction of new projects and renewal of leases of existing projects, and dismantling power lines, wind turbines, and solar panels in and around critical habitats.

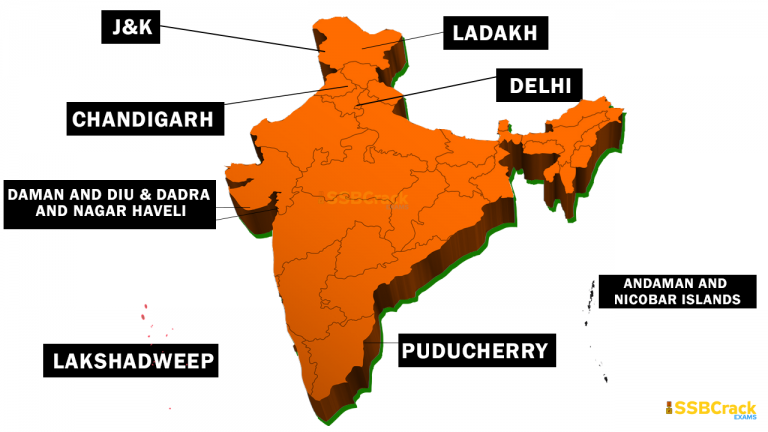

- The apex court was considering an appeal for the modification of its April 19, 2021 order, which imposed restrictions on the setting up of overhead transmission lines in a territory of about 99,000 sq km in the GIB habitat in Rajasthan and Gujarat.

- Ministry of Power, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, and the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy had filed the application to modify the 2021 order on grounds that it had adverse implications for India’s power sector, and that undergrounding power lines was not possible.

- The three ministries also cited India’s commitments on transition to non-fossil fuel energy sources vis-à-vis the Paris climate treaty as one of the key grounds for seeking a modification of the 2021 order.

SC Judgement

- The apex court modified its April 2021 order giving directions for underground high-voltage and low-voltage power lines, and directed experts to assess the feasibility of undergrounding power lines in specific areas after considering factors such as terrain, population density, and infrastructure requirements.

- The ruling acknowledged that its earlier directions, “besides not being feasible to implement, would also not result in achieving its stated purpose, i.e., the conservation of the GIB”.

- In essence, the ruling put the apex court’s stamp of approval on the Union’s affidavit on steps “for the conservation and protection” of the GIB.

- Referring to environment-related aspects of the Directive Principles of State Policy, the court said that these have to be read together with the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21.

- The SC has historically acknowledged Article 21 as the heart of the fundamental rights in the Constitution. The SC has said that the right to life is not just mere existence, but that it includes all rights that make it a meaningful and dignified existence for an individual.

- In the 1980s, the SC read the right to a clean environment as part of Article 21. A bundle of rights — including the right to education, the right to shelter (in the context of slum dwellers), the right to clean air, the right to livelihood (in the context of hawkers), and the right to medical care — have all been included under the umbrella of Article 21.

- However, these “new” rights cannot be immediately materialised or exercised by a citizen. Despite the plethora of environmental rights cases, clean air is still a pressing concern.

- Such rights are actualised only when policies are framed and legislation enacted. While dwelling on India’s international commitments to mitigate the impact of greenhouse gas emissions, the apex court also noted that despite many regulations and policies to address the adverse effects of climate change, there was no single legislation relating to climate change and attendant concerns.

- However, the absence of such legislation, the Bench said, did not mean that Indians do not have a “right against adverse effects of climate change”.

- Environmental lawyer Ritwick Dutta said that the apex court’s judgment puts the focus on strengthening environmental and climate justice by elucidating the multiple impacts of climate change on a range of communities.

- “A significant aspect of the judgment is the expansion of Article 14. Over the last few decades, the right to life has been expanded by the apex court to include a right to clean environment. The judgment not only looks to curb environmental pollution, but also proactively outlines environmental and climate justice issues, keeping our international commitments in mind,” Dutta said.

- The Supreme Court has on several occasions in the past few decades relied on the Constitution to uphold human rights pertaining to environmental issues. This includes rights such as the right to live in a healthy environment, to enjoy pollution-free water and air, to live in a pollution-free environment, etc. Typically, such recognitions signify issues of broader public interest where existing laws and policies are inadequate.

- The acknowledgment of the “right against adverse effects of climate change” by the highest court establishes a significant legal precedent,” Sinha said.

- 20th ASEAN-India Summit & 18th East Asia Summit Highlights

- Manipur Police Register Criminal Case Against Assam Rifles

- Pakistan’s Ex-PM Imran Khan Jailed For 3 Years In ‘Toshakhana Case’

- Four Years After Removal Of Art 370: How Is The Actual Situation In Kashmir?

- Putin’s Critic Alexei Navalny Sentenced To 19 More Years In Prison

- Delhi Services Bill Tabled In Lok Sabha: Govt Of NCT Of Delhi (Amendment) Act, 2023

- Gurugram Nuh Violence: How A Religious Procession Turned Into A Communal Clash

- Govt Imposes Import Restrictions On Laptops, Tablets, Computers

- How Climate Change Is Altering The Colour Of The Oceans?

- New IPCC Assessment Cycle Begins: Why Is It So Significant?

- Difference Between NATO Vs Russia? [Explained]

- Italy Regrets Joining China Belt & Road Initiative (BRI)

- What Is Doping: Why Is It Banned In Sports?

- India Tiger Census 2023: India Is Now Home To 75% Of Tigers In The World

- Military Coup In Niger – President Detained, All Institutions Suspended

- No-Confidence Motion Against PM Modi’s Government

- Elon Musk’s SpaceX Rocket Punches Hole In Ionosphere

- Israeli Parliament Passes Controversial Law Stripping Supreme Court Of Power

- Significance Of 1999 Kargil War: How It Became A Major Game Changer For Indian Military?

- Controversy Over Movie Oppenheimer Gita Scene: How Are Films Certified In India?

- The Curious Case Of Qin Gang: China’s Foreign Minister Who Went Missing

- Twitter’s Iconic Blue Bird Logo Set To Be Replaced By An X Logo

- India Pulls Out Of Games In China Over Stapled Visas For Arunachal Athletes

- PM Modi Urges Sri Lanka President To Implement 13th Amendment

- India Pulls Out Of Games In China Over Stapled Visas For Arunachal Athletes

- Rajasthan CM Sacks Minister After Remarks Over Crimes Against Rajasthan Women

- Manipur Sexual Assault: Video Sparks Outrage Across The Country

- BRICS Summit 2023 In August: Why Putin Won’t Go To South Africa For The Summit?

- Robert Oppenheimer: The Father Of Atomic Bomb, Impact Of Bhagavad Gita On Him

- Russia-Ukraine Black Sea Grain Deal, Why Russia Has Halted It?

- Henley Passport Index 2023, India Passport Ranked 80th

- Indian Opposition Parties Form ‘INDIA’ Alliance, 26 Parties Unite For 2024

- Britain Joins Asia-Pacific Trade Group ‘CPTPP’ – Biggest Trade Deal Since UK Left EU

- NITI Aayog Report On National Multidimensional Poverty Index

- PM Modi UAE Visit: Highlights & Key Takeaways

- PM Modi’s Visit To France: Highlights & Key Takeaways

- NATO Summit Vilnius 2023: Highlights & Key Takeaways

- Turkey Supports Sweden’s Bid For NATO Membership At Vilnius Summit 2023

- Why ISRO Wants To Explore The Moon’s South Pole: Chandrayaan-3 Mission

- Bengal’s Panchayat Polls Turned Violent: SSB Interview Topic 2023

- First Ever IIT Campus Outside India In Tanzania

- RBI’s Report On “Internationalisation Of Rupee” Why And What Are The Benefits?

- Japan To Release Nuclear Wastewater Into Ocean – Gets Approval From IAEA

- PM Modi Chairs 23rd SCO Summit: Highlights & Key Takeaways

- Israel Raids Jenin Camp: Massive Military Operation In West Bank

- Dutch King Apologizes For Netherlands’ Role In Slavery: A Look At The Dutch Role In History

- Constitutional Crisis In Tamil Nadu: The Tussle Between Governor & DMK Government

- Why Has France Been Engulfed By Protests Again?

- Paris Summit – World Leaders Unite For A New Global Financing Pact

- India Ranked 67th On Energy Transition Index – Sweden On Top Of List By World Economic Forum

- Four Minor Planets Named After Indian Scientists

- NASA Recovers 98% Water From Urine & Sweat On ISS: Breakthrough In Long Space Missions

- ESA Space Telescope Euclid Is All Set For Launch To Observe Dark Side Of Universe

- PM Modi’s Trip To USA: Key Takeaways & Highlights

- PM Modi-Led Yoga Session Creates A New Guinness World Record

- Sajid Mir, The Mastermind Behind 26/11 – His Designation As Global Terrorist Blocked By China

- UN Adopts First Historic ‘High Seas Treaty’ To Protect Marine Life

- International Yoga Day 2023 – How It Was Celebrated Across The World?

- Gender Apartheid – Why Is Afghanistan At Stand Off With UN?

- Gandhi Peace Prize 2021 For Gita Press Why It Triggered A Congress-BJP Brawl?

- The New Pride Flag – Why The Change & What The Colours Signify?

- 48 Years Of Emergency – PM Modi Refers It As India’s Darkest Period In Mann Ki Baat

- Groundwater Extraction Has Tilted Earth’s Spin – How Will It Impact The Climate Change?

- Europe’s Worst Migrant Boat Disaster – 78 Dead, Hundreds Missing Off Greek Coast

- MOVEit Global Hacking Attack – Government Agencies In The USA Targeted

- Karnataka Govt Decides To Repeal Anti-Conversion Law: Why Was The Law Controversial?

- IIT Bombay Among Top 150 Varsities In QS Rankings 2024

- China’s Xi Jinping Backs ‘Just Cause’ Of Palestinian Statehood – Chinese Middle Eastern Diplomacy

- Turkey Won’t Back Sweden’s Bid To Join NATO – Why Is Erdogan Against Sweden’s Application

- UN Report Reveals Chronic Bias Against Women – 25% Of Population Thinks Beating Wife Justifiable

- Zinnai – Space Flower Grown On International Space Station By NASA – Why Is It Significant?

- Who Are Meira Paibis: Manipur’s ‘Torch-Bearing’ Women Activists?

- USA Set To Re-Join UN Cultural Agency UNESCO

- CoWIN Data Leak – Aadhaar, PAN Card Info, On Covid Portal, Made Public By Telegram

- $10bn Investment Deals Signed At Arab-China Summit – Is Arab World Moving Towards China?

- Cyclone Biparjoy Turns Into Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storm – 10 Points To Know

- PM Modi’s Trip To Egypt: Highlights & Key Takeaways

- El Nino Returns After 7 Years: Will Impact Second Half Of Monsoon

- Europe’s Copernicus Programme Completes 25 Years: SSB Interview Topic

- Trump Charged Over Secret Documents In A First For An Ex-US President

- 39 Years Since Operation Bluestar: What Actually Happened?

- Wagner Chief Vows To Topple Russian Military Leaders

- Arctic Could Be Ice-Free In The Summer By 2030: SSB Interview Topic

- PM Modi’s School In Gujarat Will Host Students From Across India

- Major Dam Collapse In Ukraine – Accuses Russia Of Blowing Up Kakhovka Dam

- Microsoft To Pay $20 Million For Illegally Collecting Children’s Info

- NIRF Ranking 2023: IIT Madras Tops The List For 5th Consecutive Year

- TRAI’s ‘Digital Consent Acquisition’ (DCA) Facility’- Unified Platform For Customers’ Consent

- 34th Anniversary Of Tiananmen Square Protest – Hong Kong Police Detains Activists

- Asia Security Summit 2023 Shangri-La Dialogue Begins Amid China-US Tensions

- Coromandel Express Accident – How 3 Trains Derailed, Crashed At Same Place In Odisha

- Law Commission Against Scrapping Of Sedition Law, Says It Will Protect India’s Unity

- Radical Changes In NCERT Textbooks – Poverty, Inequality, Democracy Among Topics Removed

- India GDP Data Beats Expectations – Stays Fastest Growing Economy

- Maharashtra’s Ahmednagar To Be Renamed Ahilyanagar

- Scientists Discover 2nd Moon Near Earth Orbiting Since 100 BC

- Erdogan’s Victory In Turkish Election – What Can Be The Impact On India?

- NASA Alert! GIANT Asteroid Racing Towards Earth

- Uganda Signs Anti-Gay Law With Death Penalty – Sparks Global Outrage

- RBI’s ‘Lightweight’ Payments System For Emergencies – An Alternative To UPI, NEFT, RTGS

- Significance Of ISRO’s Newly Launched NavIC Satellite In Regional Navigation

- What Is The Model Prisons Act – Reforms In The Indian Prisons System?

- Global Plastic Treaty – Negotiations Underway For A Plastic-Free Planet: SSB Interview Topic

- China Sends First Civilian Astronaut To Space As Shenzhou-16 Blasts Off

- US Congressional Panel Suggests Making India Part Of NATO Plus: SSB Interview Topic

- India Conducts National Cyber Defence Exercise

- What Is XPoSat, India’s First Polarimetry Mission?

- Germany Falls Into Recession As Inflation Hits Economy

- Bangladesh Faces Fuel Crisis – Dollar Shortage Issue

- Australian Universities Ban Student Applications From Certain Indian States

- What Is Volt Typhoon: China-Backed Hackers Targeting USA?

- Death Of Six Cheetahs At Kuno National Park: SSB Interview Topic 2023

- India-Australia Relations Get Stronger – What Is Migration Deal?

- What Is Sengol: To Be Placed In The New Parliament Building?

- Annual Misery Index – India Ranks 103 Out Of 157 Nations: SSB Interview Topic

- Russia Pressures India For Help To Avoid Getting Blacklisted By FATF

- What Is Mission LiFE – How It Will Fight Against Climate Change?

- What Is The ‘Pandemic Treaty’: How WHO Could Fight Future Pandemics?

- Assam CM Himanta Biswa Sarma Announces Withdrawal Of AFSPA

- El Nino Could Hit World Economy By $3 Trillion? SSB Interview Topic 2023

- Tussle Between Delhi Govt And Centre – Delhi Ordinance Issue: SSB Interview Topic

- China Braces For New Covid Wave With Up To 65 Million Weekly Cases

- Colour-Coded Warnings By The IMD: SSB Interview Topic 2023

- Saudi Scripts History As First Arab Woman Astronaut Lifts Off Into Space

- Controversy Behind Inauguration Of Parliament Building: SSB Interview GD Topic

- Uniform Civil Code: Is Time Ripe For the Indian Government To Act On It?

- Indian-Origin Ajay Banga To Be The Next World Bank President

- AI ‘Godfather’ Geoffrey Hinton Quits Google Warns Of Danger Ahead

- India Ranks 161 Out Of 180 Countries – World Press Freedom Index

- Supreme Court Rules It Can Directly Grant Divorce To Couples: SSB Interview GD Topic

- Kashmir All Set To Hold G20 Summit In India

- Go First Airlines Files For Insolvency: SSB GD Topic

- India Becomes Europe’s Largest Supplier Of Refined Fuels

- What Is The Met Gala – Fashion’s Biggest Night?

- Clashes In France Against Pension Reforms By Macron Govt

- Why Are Indian Wrestlers Protesting Against WFI Chief?

- China Offers Ukraine To Mediate To End War With Russia

- 50 Years Of Kesavananda Bharati Case: SSB Interview Lecturette Topic

- Assam-Arunachal Pradesh Border Dispute: SSB Interview Lecturette Topic 2023

- Same-Sex Marriages In India: Key Supreme Court Verdicts On LGBTQ Rights

- What Is China Plus One? SSB Interview Lecturette Topic 2023

- India-Maldives Relations: SSB Interview Lecturette Topic 2023

- India-Bangladesh Relations: SSB Interview Lecturette Topic 2023

- India-Japan Relation: SSB Interview Lecturette Topic 2023

- Geopolitical Importance Of The Indian Ocean: SSB Interview Lecturette Topic 2023

- All About Paris Club: SSB Interview Lecturette Topic

- PM Narendra Modi Has Been Named The Most Popular Leader In The World

- Hindenburg Report On Adani – Here’s What You Need To Know

- India At WEF Davos Summit 2023: Here Are 10 Key Highlights

- Pakistan Economic Crisis 2023: SSB Interview Topic [Fully Explained]

- Joshimath Crisis: What Does “Land Subsidence” Mean, And Why Does It Happen?

- Top 10 Animal Conservation Projects In India [MUST WATCH]

- What Is Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Summit 2022? [Fully Explained]

- 20 SSB Interview Questions On Russia Ukraine Crisis

- What Is The (India-Israel-UAE-USA) I2U2 Summit? [Fully Explained]

- What Is International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC)?

- What Is Sri Lankan Crisis? [Fully Explained]

- What Is The BIMSTEC Grouping And How Is It Significant? [EXPLAINED]

- What Is The Places Of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991? [Explained]

- What Is Bodo Accord | SSB Interview Notes [Fully Explained]

- What Is AFSPA: Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act?

- What Is G20 Or Group Of Twenty Countries?

- What Is AFSPA: Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act?

- What Is The Financial Action Task Force (FATF)? [Fully Explained]

- What Is Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD)?

- Difference Between NATO Vs Russia [Expained]

- What Is United Nations Security Council (UNSC) [Explained]

- Everything You Need To Know About SAARC: South Asian Association For Regional Cooperation

- All About Russia Ukraine War: SSB Interview Topic [Fully Explained]